Making a strategic board game around the karmic universe is a great idea. Letting Marco Bucci unfold the visual landscape is an equally great idea. Following the hemispheregames duo Eddy Boxerman and Dave Burke leads us to the upcoming card game Karmaka. Eddy and Dave has been praised for their digital game Osmos.

The art of Karmaka is vivid and captivating. Karmaka defiantly takes an untraditional direction in its visual landscape. This is what Marco Bucci from Toronto, Canada, tells us about his work.

Color and light seems like one of your passions. How do you find the Karmaka color’s and when did you decide on the card distinction with color?

Yes, you’re totally right: capturing color and light is the reason I paint! The paintings in Karmaka were interesting because they came with an inherent limitation.

That is, each card had to belong to an overall color set (red, green, or blue). The concept of these “color sets” was in the game right from the start, before I came on as its illustrator.

As an illustrator, I am used to using fairly expansive palettes to create mood, and strive to balance color’s as tastefully as I can – but Karmaka was asking for unbalanced palettes. So, how to do this while still producing a compelling image? My first attempt was overdone. I made the images too green, blue, and red. They basically looked like a grayscale painting with a photoshop filter on it (boring!) So that didn’t work.

My eventual solution was to bring back just enough variety in the colour temperatures to make the images feel as though they have an expansive palette, but in reality it’s mostly variations of grays within one color family.

Your painting style looks very traditional. How did you learn to paint? And do you paint more digital or non-digital today?

My digital painting process is directly informed by my training in traditional media. I started out painting in oil, doing piles and piles of head studies. From there, I got into plein air painting (painting from nature). I learned how color works by mixing physical pigments on a palette and applying them to a real canvas. Sadly, I think learning that way is going away as each new crop of artist is more and more mired (and seduced) by technology.

I actually think you can become a better artist by learning traditional media because it forces you to reconcile with limitations. It sharpens your eye and mind when you’re forced to use limited means to produce a strong effect. Not only that, but you’re dealing with risk, too. Materials are expensive – what if this painting doesn’t work out? This kind of training strengthens your resolve.

I actually think you can become a better artist by learning traditional media because it forces you to reconcile with limitations

You can apply all this directly to the digital world. At that point, you can see digital tools for just that – tools. And you’ll have a broader wisdom with which to use them. Having said that, I paint more digitally today than I do traditional. But it’s not due to preference. Digital is simply easier to access: I just roll out of bed and turn on my computer – it’s always there for me. Traditional media requires setup, messy clean-ups, and more time. Also, most of my jobs are digital – that’s just the way the industry is now.

At a certain point, I tend to get a little stir-crazy when I’ve been painting too much digitally. That’s when I’ll bust out the oils, watercolours, gouaches or acrylics and do some real, physical, tangible paintings. I use traditional media exclusively when I travel, too. I either carry around a little gouache sketchbook, or a larger watercolor setup. It’s a balance I constantly try to maintain.

What software do you use?

I think all painting softwares are good. I use Photoshop just because I’ve grown so used to it.

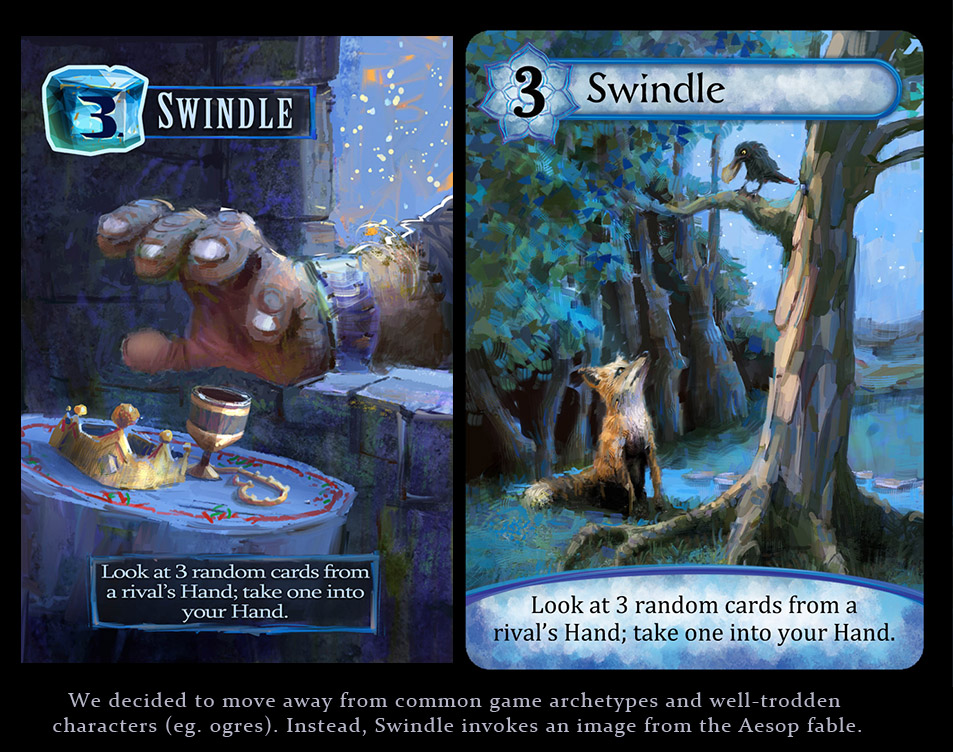

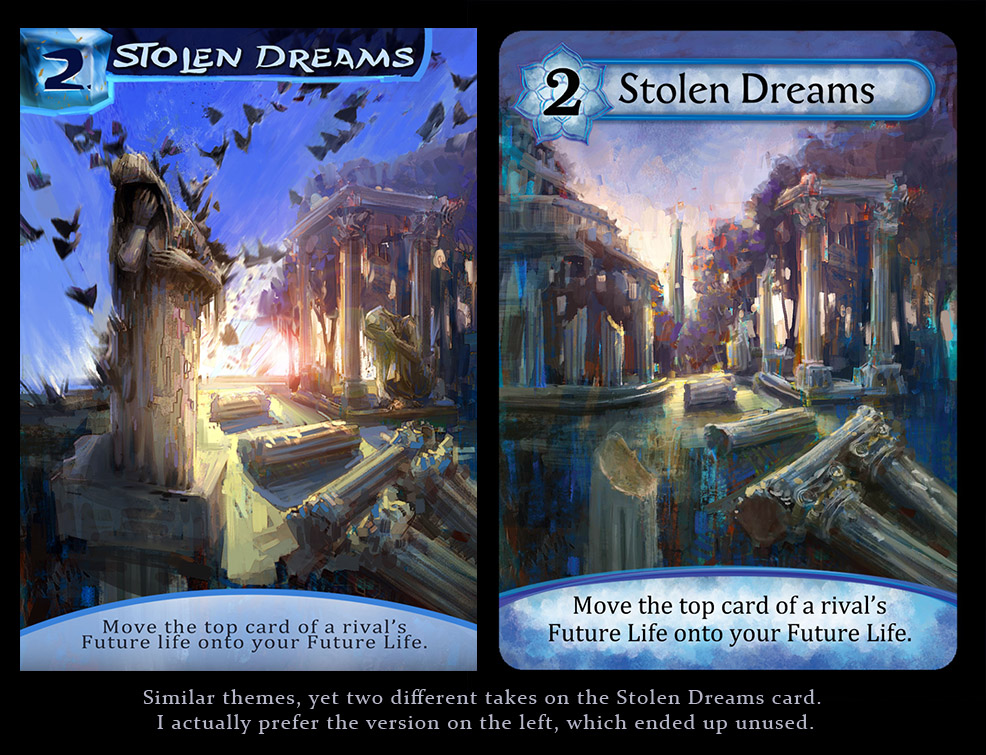

Some of Your art for Karmaka has been through many revisions. Some which added more detail to the images and some which changed the image completely. How much do you think about having equal detail and stroke types? And how much time goes into making the initial first version of a card?

In Karmaka, a lot of initial effort was spent off the canvas, brainstorming ideas for what the card titles meant. Spite, Stolen Dreams, Hell’s Heart – how do you distill those concepts into one simple picture? Once Dave and Eddy (KARMAKA creators) and I felt like we had a solid lead on that, I opened a new canvas and brain-dumped onto it. In this initial stage of painting, I don’t care about detail, brushwork, or any other thing that makes the image look pretty. I only care that a picture is forming that I can then use to take the creative conversation to the next level.

That step takes about 3-4 hours, on average.

In this initial stage of painting, I don’t care about detail, brushwork, or any other thing that makes the image look pretty.

If the initial idea was communicating, that was a great leap forward. Dave and Eddy would provide valuable feedback as to how to proceed, then I’d dive back in for my next pass, which is when I’d add in all the carefully crafted brushwork and detail for an overall finish. This often takes double the amount of time of the initial pass! If a card needed to begin from scratch, then I’d simply begin again, but using the failed card as a compass. Sometimes the initial sketch is good conceptually, but still needs to be repainted to sell it better.

There were only three cards in all of KARMAKA that essentially went unchanged from first draft to final (minor touch-ups notwithstanding). The others all went down tortuous paths of discovery (some of which started over from scratch even after we thought we had them finished!)

Could you roughly describe your workflow on your game illustrations. From start to the final image.

Hmm. It ranges wildly, depending on the client and project. Some clients give me tons of reference and direction, and I have to go through multi-tiered approvals of rough sketches before painting the final. Other times (like on KARMAKA), it’s more open-ended and I essentially just explore until we hit upon something. Sometimes I start with line drawings, while other times I just dive right in with paint and full color. Part of the professional artist’s skillset is to be diverse, so I adapt my process based on the project and client’s needs.

When you paint digital do you mimic traditional mediums by for example, keeping all on one layer without erasing but painting over or do you use many layers or use the tools available as screen and multiply effects?

In general, I like to keep my digital files as simple as possible. If I can do everything on one layer, I will. That’s my ideal. But digital tools are indispensable for more “risky” effects and overall changes, so that’s when I’ll use Photoshop’s layers, adjustment layers, filters, etc. My favourite way to use layers is to “audition” a painting change. For example on Karmaka, maybe I want the dung beetle’s dungball to be larger, but I don’t want to risk painting over my nice background. So I’ll put that on a layer. Then if I like it, I’ll commit to it and flatten everything down and continue.

One thing I always try to stay militant about is the finality of decision-making. Once I’ve committed to something, I’ve committed. If that means flattening layers, then I do it. Being too soft on this can result in tons of layers and you can quickly cripple yourself as a result of your own indecision.

One thing I always try to stay militant about is the finality of decision-making.

What art piece in Karmaka is your personal favorite?

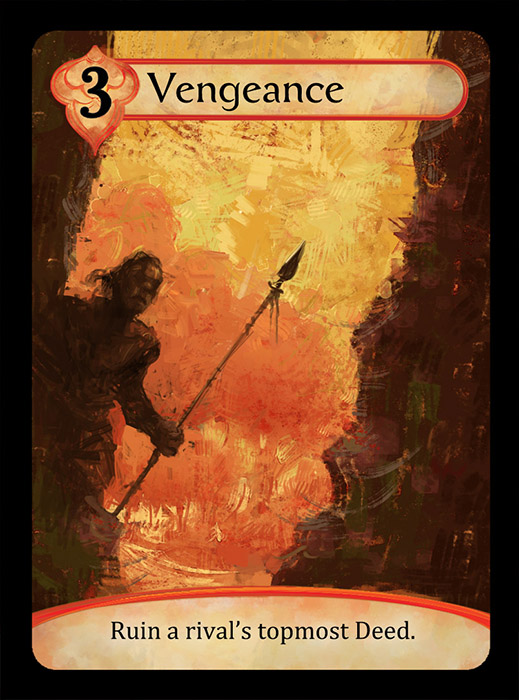

Funny thing: my favourite pieces are never the same ones the public seems to like most. I’ve always loved the Vengeance card. It has a simple, bold, V-shaped composition with tons of fun texture in the negative space. The cave and the figure melt together into one dark shape. The painting is just two shapes, yet I think it reads quite powerfully. It’s a real painter’s painting, that one.

I also like Mimic, because I enjoy how the background and foreground almost merge in color and value, but with just enough form for things to pop. It was a tough balance to pull that off.

In terms of portfolio, I think the box is technically the strongest piece. But it’s not a fair comparison because the box art is larger, with so much more breathing room. I could do more with it, where the cards are smaller, and hyper-focused on just one thing.

Can you name one of your own favourite artists?

John Singer Sargent. He’s maybe my favourite painter who ever lived. He just understood everything so intrinsically and thoroughly that each stroke he made meant so much. There were no wasted brushstrokes. It’s something I’ll always aspire to.

Finally – is there any place of inspiration, creative tutorials, or other resources you can advocate to aspiring artists?

The internet is full of good resources. You can get a lot of art industry-related stuff at The Gnomon Workshop or Schoolism. You can get awesome fine art videos at Liliedahl. You can find some of my own video workshops -both digital and traditional – at SVSlearn.com or from my website (marcobucci.com) or my YouTube channel. But I’ll always maintain that the best resource is nature. Just get outside and paint. You’ll learn so much, I promise. And the best part about nature is: it’s free.

We appreciate and thank Marco for this elaborate story. If you are interested to dive deeper into the creation of Karmaka we can recommend Marco own article on the Hemispheregames blog